Transformation makes us cringe

Unless you’re transforming Transformers, transformation tends to make use cringe. What do I mean by that?

Transformation is a four-syllable synonym for change – and change comes all the time. Whether it’s in the form of government policies (hello, TAEPP), company initiatives (back to office mandates), or even changes in friendships (someone moving away) – we see transformation all the time.

Most people either panic, or are indifferent to it.

But if change happens all the time – is it wise to always be panicking and/or being indifferent to it? More importantly, why do we panic when we see change?

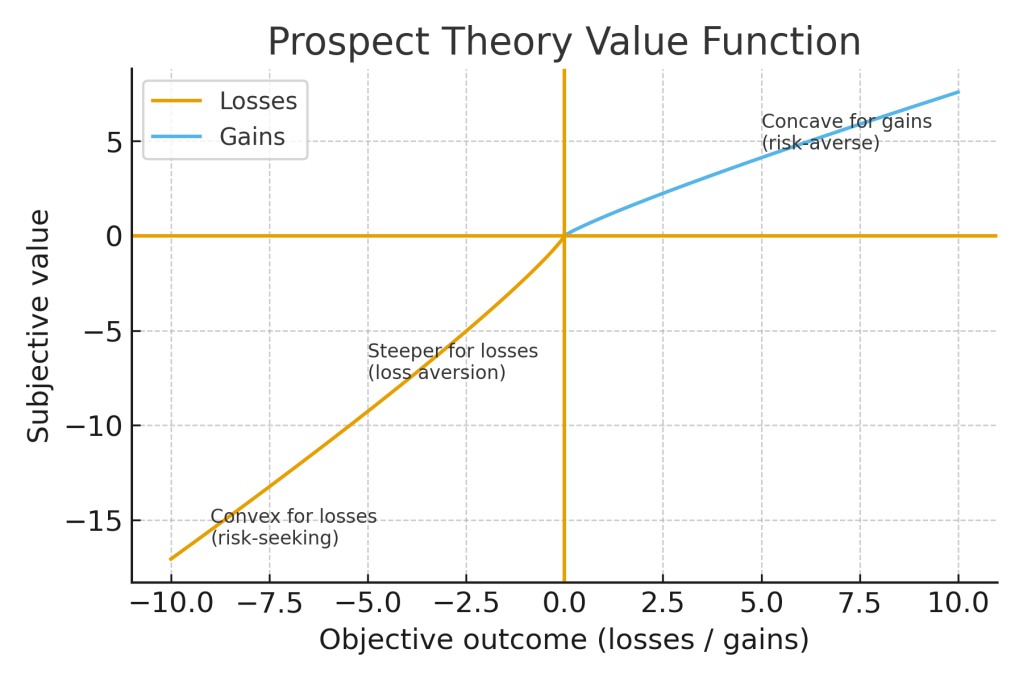

It’s because of prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), which is about how we consider losses and gains. It’s about the psychology of utility and cost, and it’s not a linear relationship.

Prospect theory explained

When I first head about prospect theory, I thought it was related to mining. Like, you know, a prospector?

It’s actually behavioural economics. It’s about how we actually make decisions when faced with risk (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) (and not how we should make decisions as rational human beings) (because we’re not rational).

The idea is that we judge all gains and all losses relative to a certain status quo in our head. This is usually what’s current for us – current government stances, current company standards, current friendship statuses.

The thing is, a loss is twice as painful as the pleasure from a gain, even if they’re the same value. So losing $10 hurts twice as much as the happiness from gaining $10. You can see that from the Prospect Theory Graph above.

That’s why we’re loss-averse creatures.

Additionally, we also experience diminishing marginal returns and diminishing marginal cost. This means the the effect of losing/gaining $100 will be impactful the first time, but the 10th time it happens, the impact will be much less.

If you’ve ever held on to your streaming subscription because the loss (going through the hassle of cancelling your subscription) seems so much more than the gain (saving about $120+ a year), then that’s prospect theory at work.

And it links to status quo bias.

Status quo bias

Status quo bias exactly as it sounds – our tendency to stay with whatever the current state of affairs is, even when there are objectively better alternatives available (Samuelson & Zeckhauser, 1988).

The link to prospect theory is this. Transformation and change feel like losses, because can lose status, familiarity, and competence. Yes, we sometimes have things to gain from transformation and change, but the loss feels much more than the gains.

In terms of the workplace, it means that employees often want to keep their current position and preserve the status quo, rather than gaining uncertain and unpredictable benefits from change (Adriaenssen & Johannessen, 2016). This means things like implementing new software (SAP, anyone?) or social reforms at the workplace (reduce WFH days).

Change, energy, and cognitive bandwidth

The problem with prospect theory is that it makes us interpret loss as a threat. Yeah, it might be a mild threat, but it’s still a threat. Our body and mind then react to it as a threat, creating stress, reducing creativity, and derailing our focus.

When that happens, we lose productivity. Productivity is not about doing more things in the same amount of time, it’s about doing the aligned things with aligned energy to create easeful flow.

What does positive psychology have to say about productivity? Firstly, high wellbeing and positive affect lead to better performance and higher productivity at work (Martínez-Martínez et al., 2025). Secondly, having more psychological capital (things like hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism) leads to better performance and more helpful, prosocial behaviours at work (Avey et al., 2011).

So it’s clear that prospect theory impacts our wellbeing. That means we need to shift our framing of change. When we do that, we’ll free up cognitive resources, reduce resistance and “stuckness”, and create the space for the meaningful work we want to do.

Using positive psychology to deflect loss aversion

Here are three ways that you can redirect the nervous energy that prospect theory brings and use it to embrace and leverage change for your benefit.

1. Reframe the reference point: Use journalling and describe your future self (or even your Best Possible Self) a few years after the change. This shifts your framing so that you’re not seeing the change as a loss, but as a way to move forward to desired stability. You can also journal it as “This change might feel like I’m losing [something], but I’m actually gaining [another thing].”

2. Magnify the gain and minimise the loss: Tell yourself “let’s test this for 2 weeks” before reacting. Use that time to gather data and treat it like an experiment. By putting an end date and thinking of it as a fact-finding exercise, it gives you time to adjust the baseline (remember Prospect Theory) so that when you’re aware of the change again, it comes from a different place.

3. Protect your self-determination: Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985) states that we need autonomy, competence, and relatedness for engagement. So work on these three pillars. Create choice within the constraints of change for autonomy (such as decided how to get to the outcome, rather than what the outcome is), use social support for relatedness (accountability buddies or even just people to talk to), and build your competence (learn about the change one aspect at a time, rather than all at one go).

Change is inevitable, but your response is not.

Prospect theory might make it seem like our responses are programmed and unchangeable, but it actually just means that our reactions are predictable. So if you know what’s going to happen, you know how to design around it and design for it.

We feel loss much greater than we feel pain, but we can change the start points of where we feel that loss/gain, and we can rely on other pillars of wellbeing to support us through change.

What is one change that you’re currently resisting?

You might also want to read:

References

Adriaenssen, D. J. & Johannessen, J. (2016). Prospect theory as an

explanation for resistance to organizational change: some management

implications. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 14(2), 84-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.21511/ppm.14(2).2016.09

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Martínez-Martínez, K., et al. (2025). Systematic review and meta-analysis of positive psychology interventions in workplace settings. Social Sciences, 14(8), 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080481

Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1(1), 7–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00055564

Leave a comment