Autopilot isn’t always awesome

I’m a fan of automation. Standardised workflows. SOPs. Muscle memory. To me, this is efficient, because it frees up your mind space for other, more productive endeavours.

And that’s what I used to do. When I take a bath, I clean myself in a very set routine so I can devote the time to shower thoughts. When I used to drive, I already knew the exact route to my workplace so I could free up the headspace for thinking about how to approach that day’s task. When I take the MRT to familiar destinations, I autopilot to the exact door and side of the train station.

But when there’s an MRT breakdown – a disruption to the routine – it throws my automation into chaos. My carefully segmented schedule (I do my social media tasks while on the train) needs to be hastily rewired. I post the wrong things on social media and head to Punggol instead of Outram by mistake.

And that’s the issue with too much automaticity. We lose the mindfulness and intentionality behind it, and we can’t adjust to disruptions.

I’m not saying that automation is bad. What I’m advocating is mindful workflows, rather than mindless automation. Mindful workflows give us constructive productivity, whereas mindless automation is dialling it in but not necessarily making progress.

What is automaticity, and why do our brains like it so much?

Firstly, what is automaticity? It refers to the ability to perform a task without the need for executive control (Foerde & Poldrack, 2009). It’s not a concern if you’re single-tasking. But honestly, who is single-tasking nowadays? It’s more of a concern when you’re multi-tasking, which we do all the time now.

If your performance of a skill is insensitive to interference from a secondary task, then it is considered automatic (Foerde & Poldrack, 2009). What this means is that if you can do task B doesn’t interfere with how you perform task A, then task A is considered to be automatic.

It’s great because it frees up cognitive for more complex tasks (Bargh, 1994). You can type in your password while half-asleep. You can travel home without concentrating on every single step. You can take a shower without drowning.

But when too many things are automatic – then where does your attention go? Worse still, this over-reliance on automaticity makes us less adaptable in dynamic environments (Christoff, 2025). We stop focusing, being mindful, and being present.

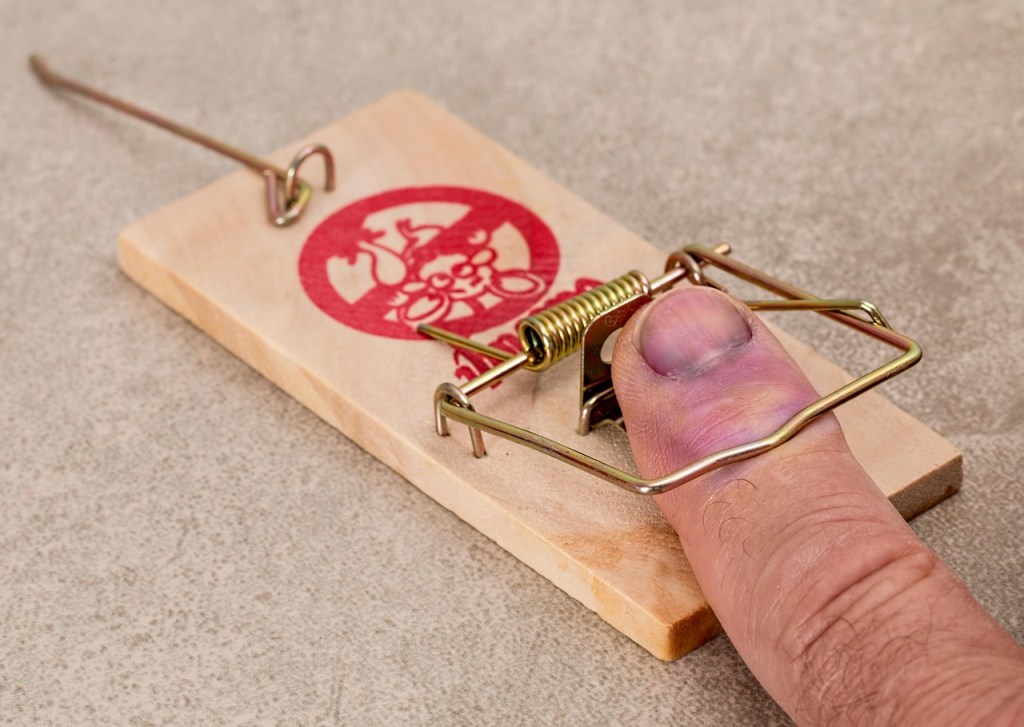

Automaticity – the hidden productivity trap

Okay I love my own automaticity but the hard truth is this.

Automaticity doesn’t make you more productive – it makes you more busy.

And while yes, you are a busy person – what you really want is productivity, right? But what you actually get are the following “benefits”:

- Zombie workflows: You do things the same way over and over again even if it doesn’t serve your goals, because “it’s how it’s always been done”

- Rigidity problems: Your routines don’t change when life changes, and life always changes

- Disengagement: When you’re not present in your tasks, then you lose the meaning and motivation behind it

But automaticity isn’t all bad, right?

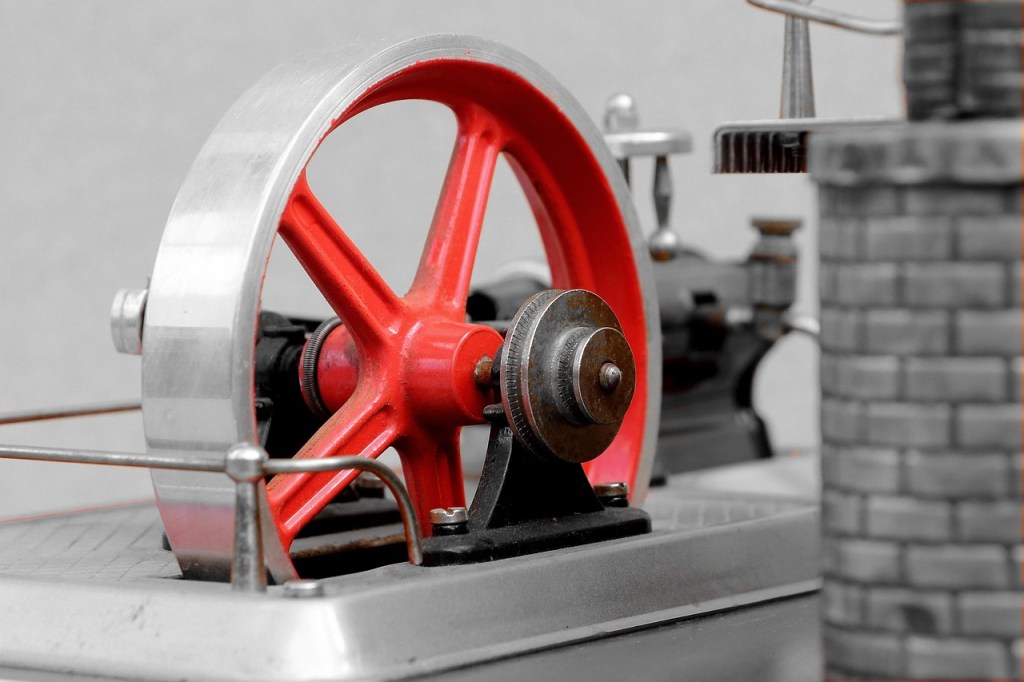

No, it’s not. Automaticity is great when it comes to habits. Habits are the “enormous fly-wheel of society”, as William James (1890) said. A fly-wheel doesn’t have anything to do with houseflies, it’s actually a mechanical engineering device. It’s like a spinning disk that’s heavy and attached to an engine. Once you start spinning it, it keeps spinning and resists sudden changes in speed. It helps to keep motion steady, because it balances out sudden acceleration and pauses in the engine’s movement.

Habits are essential for efficiency (the good kind), otherwise we’d be wasting precious mental energy trying to actively and consciously poop (or hold in poop) all day along. More saliently:

- Habits keep us stable: Our actions keep moving smoothly without needing much effort or conscious control, valuable for good habits

- Habits resist change: It’s hard to stop and start our habits, which means that while habits take effort to build, they can also be hard to break

- Habits conserve energy: They reduce the initiating energy we need to start things, and let us use our mental (and physical) energies for other, more complex tasks

This leads on to secret key (no lah, it’s not SKII) to leveraging automaticity. Intentionality.

Automating mindfully

This is where positive psychology saves the day. Automation can be good when it serves your values.

Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) states that people thrive when their actions align with intrinsic goals. Intrinsic goal are things like growth, connection, and meaning.

When you mindlessly automate, you take that alignment away. But when you mindfully automate, you gain alignment. A simple example is this:

- Automating bill payments? Yes of course.

- Automating creative brainstorming? That’s a huge mistake.

The guideline is this – will automating this make me more of who I want to be? If it does, then go ahead. If not, then although it will take you more time to perform that task, it’s better to stay in the present and do it.

The antidote to unwanted automaticity

The thing about automaticity is that it doesn’t just takes your attention away from tasks. It takes away your attention to people. You know, the living, breathing two-legged creatures that we’re surrounded by and love?

When you hear someone say “I told you this already!” and you haven’t heard it before – you’re on autopilot listening. Automaticity narrows your attention so much that you no longer notice the opportunities, relationships, joy, and people around you.

Fortunately, there is an antidote – savouring. Savouring is the act of paying attention (there’s that magic word again!) to the good things in your life (Bryant & Veroff, 2007), such as conversations, small wins, and the present moment.

When you savour, when you pay attention – there’s a productivity payoff.

- Better collaboration

- Fewer mistakes

- More creativity and intelligence

To be more present and notice things isn’t “wasting time”. It’s “saving time” because that’s where true innovation comes from.

Creating rugged but flexible workflows

Brad Stulberg’s (2023) Master of Change illuminated this principle of rugged flexibility. And that’s a principle we can apply to workflows. Your workflows should be able to survive storms (a key person quitting, for example) but also be able to bend when conditions change.

You should be able to swap tasks based on energy levels, emergencies, and shifting priorities. However, things like your morning planning routine, or shutdown rituals for the end of the day should still hold. It’s about flexible goal pursuit, which is linked to greater wellbeing (Wrosh et al., 2003). It makes you better.

But of course, there are plenty of other benefits for mindful workflows, such as:

- Alignment with values: stronger motivation and engagement

- Reduced wasted effort: fewer irrelevant, outdated, automated tasks

- Resilience under change: mindful adaptation, selective autopilot functioning

- Better cognitive performance: even brief mindfulness improves executive functioning and task flexibility, making you smarter (Zeidan et al., 2010)

So plan hard, but hold soft.

Practical ways to mindfully automate

Again, automaticity isn’t bad. So can we make automaticity work for us in a mindful manner?

- Audit workflows: Take time to physically write down what you have automated and ask: “does this serve me, or do I serve it?”

- Insert awareness triggers: The pause between stimulus and response is key, as Viktor Frankly reminds us, so even a simple reminder or Post-It note asking “does this matter?” will help.

- Check if it aligns with your values: Before you automate something, consider this: does this reflect who I want to be?

- Micro-mindfulness: Take one deep breath and set your intention before you begin a task. “What do I want to accomplish from this?”

- Automate the mechanical but not the meaningful: You can schedule emails. but not schedule personal messages to friends.

On that last point – yes, I’ve done it before (to a friend who doesn’t live here). I think it became obvious when the message looked exactly the same on the same day of every month. We’re still friends, but if you know who you are, I’m sorry. I wanted to keep in touch, but it wasn’t the best way to go about it.

Build systems that you notice – and that notice you

We’re not robots. I mean, yes, I like Transformers, but they are sentient robots. I’m talking about non-sentient robots.

We’re meaning-making humans. We’re not machines. The systems we build should notice us and change according to our circumstances. Automaticity is great for putting on our shoes.

But when it takes over our life, when it robs of awareness, when it takes away our adaptability, when it disables joy… yeah. That’s an issue.

Building workflows with rugged flexibility and creating mindful automation is the key to that. It’s the key to stop automaticity from taking over your life.

So don’t own autopilot your whole life. Your systems should let you notice, adapt, and thrive. Because we’re humans. We’re not machines.

References

Bargh, J. A. (1994). The four horsemen of automaticity: Awareness, intention, efficiency, and control in social cognition. In R. S. Wyer, Jr. & T. K. Srull (Eds.), Handbook of social cognition: Basic processes; Applications (2nd ed., pp. 1–40). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Bryant, F. B., & Veroff, J. (2007). Savoring: A new model of positive experience. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Christoff Hadjiilieva K. (2025). Mindfulness as a Way of Reducing Automatic Constraints on Thought. Biological psychiatry. Cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging, 10(4), 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2024.11.001

Foerde, K., & Poldrack, R. A. (2009). Procedural learning in humans. In L. R. Squire (Ed.), Encyclopedia of neuroscience (pp. 1083–1091). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008045046-9.00783-X

James, W. (1890). The Principles of Psychology. New York: Henry Holt and Company the Principles of Psychology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/11059-000

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Stulberg, B. (2023). Master of change: How to excel when everything is changing—Including you. HarperOne.

Squire, L. R., Bloom, F. E., & Spitzer, N. C. (Eds.). (2009). Automaticity. In Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-045046-9.00078-3

Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., Miller, G. E., Schulz, R., & Carver, C. S. (2003). Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: goal disengagement, goal reengagement, and subjective well-being. Personality & social psychology bulletin, 29(12), 1494–1508. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203256921

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and cognition, 19(2), 597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014

Leave a comment