Too busy to decide

I like making optimal choices. But that often means a lot of overthinking, 17 browser tabs, 23 days of research – just to buy one blender (true story). And when I did buy it – did I really know if it was really the best choice? All I knew was that I spent so much time and energy on it.

This doesn’t just happen with the smaller things in life – it happens with jobs, partners, life goals, everything. We get stuck in a cycle of overthinking, second-guessing, and then regretting the decisions that we made too late. Why? Because we think that taking more time to think results in better decisions. But how feasible is that when we make 35,000 decisions a day – with 226 of those decisions about food alone (Wasink & Sobal, 2007)?

The fact is that decision regret doesn’t usually come from deciding too soon – it comes from waiting too long to make a decision.

To disclaim: I’m not advocating hasty decisions or not doing any research at all! Rather, I’m advocating a sufficient amount of research (I’ll share more about it later) than a perfect level of research.

Why we regret waiting more than acting

We tend to regret taking action (like sending hastily-written, angry texts) – in the short term.

But in the long term, we regret inaction.

We don’t regret the action of quitting that job (I don’t, at least) – we regret the inaction of having stayed in a company we hate for so long. We don’t regret the action of the risk we took – but the inaction of not having taken that risk in the first place.

When it comes to regret, there’s a temporal element to it. Action (errors of commission) generate more regret in the short term, but inaction (errors of omission) generate more regret in the long run (Gilovich & Medvec, 1995). And ultimately, it’s the long run that we’re looking at – the long game that we busy people are playing.

It’s about the missed chances – the holiday you never took, the career jump you never made, the date you didn’t ask for, the toy you didn’t buy, the words you didn’t say, the action you didn’t take.

Regret feels so painful because human beings are loss averse. Prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) explains that humans feel losses much more greatly than they feel gains. Thus, we make decisions from a place of what we could lose, rather than what we could gain – and we over-research and overthink.

But there’s a cost to that. An opportunity cost. While we’re deliberating over making the perfect choice, other people are satisficing and making “good enough” choices

Ultimately, it all boils down to this – if you delay decision-making until you can make the perfect decision, that you might not act at all and magnify your regret.

Done is better than perfect: 80% is enough

To get the top grade in O-Levels and A-Levels, you need to score at least 75% or 70%, respectively.

80% is way more than getting the best grade for O-Levels & A-Levels. 80% is more than sufficient. I’m advocating “80% is enough”.

In any case, the 80% rule is based on the Pareto Principle, also known as the law of the vital few or the principle of factor sparsity. It’s a power law distribution – for example, 80% of your sales come from 20% of your clients, or that 80% of the land is owned by 20% of the population, so on and so forth.

If you’re 80% sure, 80% of the way there, 80% up the meter – then it’s time to move. Striving for 100% certainty leads to analysis paralysis – which is the paradox of choice (Schwartz, 2004). Basically, it means that the more options you consider, the more dissatisfaction you feel.

From a neuroscience perspective, your prefrontal cortex (which is responsible for complex decision-making) follows the law of diminishing returns. The first 80% of information processing happens relatively quickly and efficiently. The final 20% requires exponentially more mental energy, while only providing very little input (comparatively) to the decision making.

It’s explained by Herbert Simon’s (1956) research on satisficing versus maximising. When it comes to satisficing (finding options that meet your criteria) and maximising (finding the absolute best option) – it’s the satisficers who are happier and more productive.

One way of doing that is to classify decisions using the framework that Jeff Bezos (2016) uses (yes, the Amazon Jeff Bezos) – Type 1 and Type 2 decisions. For him,

- Type 1 decisions: irreversible, with high stakes and high impact

- Type 2 decisions: reversible, with lower stakes and lower risk

So Type 2 (reversible) decisions can be made quickly, by people with good judgement (like yourself, dear reader) – while Type 1 (irreversible) decisions benefit from methodical, careful, and deliberate consideration.

Opportunity costs, not sunk costs

However, it’s not always just about the 80% rule.

Emotions play a big part in how we make decisions – especially when past investments are involved. It’s not just money, but time and effort, that constitute these sunk costs. Let’s say you’ve spent three years (1,095 days) on something – a business, a degree, a relationship – and it’s not working well. Do you continue since you’ve already spent over one thousand days on it?

Obviously, you shouldn’t factor that in – because those 1,095 days have been spent – there’s no getting them back. That’s the sunk cost fallacy. That’s when you’re tricked into making decisions based on the past, rather than the future.

One way to avoid that is to focus on the opportunity costs – what you would miss out in the future if you don’t take action – instead. One way to do that is to make the opportunity costs explicit and create more attractive alternatives for yourself, so you can self-de-escalate and make better choices (Harman et al., 2020).

Synder’s (2002) Hope Theory supports this through positive psychology, that focusing on the future leads to better outcomes in academics, athletics, physical health, psychological adjustment, and psychotherapy.

So weigh the opportunity costs of inaction, rather than the sunk costs of what has happened. When you don’t act, ask what this indecision is costing you in terms of potential time, energy, growth – and joy.

Treat decisions like directions

I’ve talked about what not to do – but how do we treat decisions themselves?

Decisions are not final, set-in-stone, unbreakable mandates. We must and we should make them. And that’s what I press my business consulting clients to do – make a decision, be it in terms of style or personnel or products.

But you can always change your mind later.

What you need is the decision – that direction to work with. Once you have a direction, you can always course correct. But if you don’t even have a direction, there’s no affecting momentum, objectives, resources – because you’re not even moving.

Decisions are directions, not destinations.

They’re important because direction creates movement. Movement creates action. Action creates tangible data and feedback. Data and feedback provide you with the means to craft better strategies. Better strategies improve your productivity.

Also, when you treat decisions as experiments rather than endgames, you enhance your own autonomy – a key factor for motivation and wellbeing in Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Getting advice

All good coaches will tell you this – it’s never about telling the client what to do. It’s about empowering the client to discover what they really want, why they want it, and how they want to get there.

A similar approach applies when you’re asking for advice.

A rule of thumb is to ask three or fewer people. Asking more people will yield you more information, but it also triggers social comparison (Festinger, 1954), which can ultimately lead to self-doubt in uncertain moments (like the decision you’re deliberating on).

Other advice for asking for advice is:

- Relevance: Are they competent in this topic in the first place?

- Relationship: Do they know enough of your personal context and character to provide insight on your decision?

- Perspective: Can they guide you through a good process or framework to make the decision?

The most important aspect of asking for advice, however, is to monitor your reaction when you get it. Most of the time, we’re looking for affirmation or validation, not advice – we’ve already made the decision. Emotions and decision-making are deeply intertwined (Damasio, 1994) – so your interoception (the brain’s perception and processing of internal bodily signals, like heartrate and breathing) or gut feeling, is actually valuable neural data.

Whatever decision you make is ultimately about whether you feel aligned to it.

The productivity payoff of quicker choices

So why do I advocate faster, satisficing decision-making? Because the research says so.

Every unmade decision taxes your self-control. It depletes cognitive bandwidth and creates decision fatigue (Baumeister et al., 2007).

When you make a decision, you generate action. Action creates momentum, which results in engagement, which results in flow. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990) espoused flow as a way of optimal human flourishing – doing more through positive psychology.

How to make fast, good decisions that reduce regret

We’ve talked about four approaches to making fast and good decisions – the 80% principle, looking at opportunity costs instead of sunk costs, treating decisions like directions, and what getting advice is really about.

So how does this work in real life? Here are some guidelines for how to make fast and good decisions.

1. Set a decision deadline

Work – and decision-making – expands to fill the time available for its completion (Parkinson, 1955). So setting a deadline for the decision is the best way to put boundaries around this. For me, I suggest either a temporal approach (make a decision within 48 hours) or an occurrence approach (make a decision if it comes up 3 times or more), depending on the situation.

2. Clarify your priorities

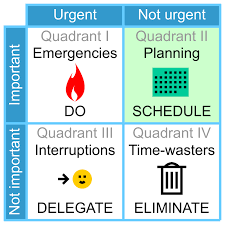

Use frameworks like the Eisenhower Matrix (urgent vs important) or the 80/20 rule to clarify what is important.

Avoid being sucked in by urgent, but unimportant tasks by stating what they are upfront.

3. Use optimal stopping theory (the best choice is after 37% of the options)

Optimal stopping theory (Ferguson, 1989), derived from the Secretary Problem, states that the best strategy for evaluation is this. After you have gone through 37% of the choices available to you, pick the next one that is better than everything else you’ve seen so far.

It’s a mathematical way of approaching your decision-making, that optimises your use of resources and the best choice available to you.

4. What would the “future me” say?

This is derived from the Best Possible Self PPI (King, 2001) – where you ask your future, ideal self what he or she would say.

This gives you some distance from the decision, increasing your perception flexibility – and allows you to don the hat of what your future circumstances and personality will be like.

5. Use your interoception – your gut feeling

Remember how Damasio (1994) found out the link between emotions and decisions? Use your interoception – the brain’s perception and processing of internal bodily signals – to monitor how your body feels. What your gut feels.

Yes, I’m asking you to ask your body how it feels about the decision – because it will give you information about what you subconsciously think of the decision.

6. Write down the fears blocking you from making the decision

Naming our fears often makes them less powerful, less overwhelming, and more concrete. It puts us in control, and puts constraints around the fear.

When you have identified your fears on paper (or a digital notebook), you will be able to better discover ways to address them – and thus, make better decisions.

7. Move quickly on reversible decisions

If your decision is a Type 2, reversible decision (using Jeff Bezos’ framework) – then make it quickly. Remember, you can change your mind and change your direction about the decision.

What’s important is to get that action, that momentum, so that you can iterate from something.

You don’t need it to be perfect – you just need a decision

In a way, making the perfect decision is like overplanning – it’s not about getting it right in the first try, it’s about moving yourself into action.

Agency, momentum, and purpose are the keys to productivity – keys that are created by action. Conversely, inaction breeds regret and hesitation.

You have the frameworks – the 80% principle, looking at opportunity costs instead of sunk costs, treating decisions like directions, and what getting advice is really about. You have the guidelines.

Whatever decision you make is the best one – so long as you make it.

You’re not shackling yourself to an unchangeable truth when you make a decision.

You’re unlocking your next chapter of life.

References

Gilovich, T., & Medvec, V. H. (1995). The experience of regret: What, when, and why.

Schwartz, B. (2004). The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less.

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes.

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.

Parkinson, C. N. (1955). Parkinson’s Law. The Economist, 177(6356), 635–637.

Ferguson, T. S. (1989). Who solved the secretary problem? Statistical Science, 4(3), 282–289.

You might also want to read:

Leave a comment