How you see it and what you see

In Avengers: Infinity War, Thanos decides to use the Infinity Gauntlet to Snap away half of the universe.

Thanos’ framing of the action is that he’s saving the entire universe. The half that survives will have enough resources, while the half that is dead… won’t suffer from a lack of resources.

The Avengers’ framing of the action is that Thanos is murdering half of the universe, killing them against their will.

It’s the same action but measured in gains (Thanos) and losses (Avengers) – and this is decision framing and prospect theory in action.

This is what powers our ability to reframe our decisions based on objective circumstances – and the difference between a productive framing and a panicky framing.

Also I do not condone Thanos’ actions, just putting it out there.

So what is framing anyway?

How we describe a situation is essentially the idea of framing. It is how we formulate or represent a decision.

Thanos’ Snap is the identical action in both examples, but the Avengers and Thanos frame it differently, leading to very different psychological outcomes. Each framing draws attention to different aspects of the situation.

For ordinary people, it’s about the idea that we change our preferences when the description (not the situation) changes, even though the underlying outcomes are the same.

Take the example of a undesirable but compulsory meeting (we’ve all been there). You can either frame it as a total waste of time, or you can frame it as an opportunity to benefit from understanding the needs of other people.

From a resilience perspective, being able to change your frames helps you with disputation and flexibility with explanatory styles.

The evidence for framing

There were three studies that show the effects of framing on decisions. Basically, when you change the frame (but not the situation) – you change the choice.

The first one was about a hypothetical Asian disease (did not know that diseases could be classified by race btw) that would kill 600 people. When provided with Choice A (200 people will be saved) or Choice B (1/3 chance that 600 people will live, 2/3 chance that 600 people will die), people picked Choice A – indicating risk aversion. When provided with Choice C (400 people will die) or Choice B (1/3 chance that 0 people will die, 2/3 chance that 600 people die), people picked Choice B – indicating risk-seeking (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981) even though Choice A & Choice C are the same thing!

The second one was about framing the choices between surgery or radiation therapy. People would pick surgery if it was presented as having a 90% chance of survival, but would not pick surgery if it was presented as having a 10% chance of mortality (McNeil et al., 1982) – even though they’re the same thing too!

The third one was about adjudicating custody of a child. Participants were given the traits of Parent A (more positive and more negative traits) and Parent B (fewer positive and fewer negative traits). When asked who they should award custody to – it went to Parent A, because there were more positive attributes. But when asked who they should deny custody to – it also went to Parent A, because there were more negative attributes. It’s the same question but framed differently, with the different outcomes.

And that connects with the basic principle of framing – that it is the passive acceptance of the formulation given (Kahneman, 2003). We see a description of a situation and we accept it without questioning it, ie. we automatically develop a perspective of a situation.

But how does that automatic perspective of a situation develop?

Thinking fast and slow

It comes down to System 1 and System 2 thinking (Stanovich & West, 2000) (betcha thought this would be a citation from Daniel Kahneman).

System 1 thinking is fast, automatic, and intuitive. It works with whatever is the most accessible – things that are put in the forefront, emotionally charged, or easy to understand. System 1 is intuitive thinking that doesn’t “see through the frame”.

System 2 thinking is slower and deliberate. But it is more effortful and it doesn’t activate unless we cue or motivate it. System 2 is deliberate thinking that has the power to “see through the frame”.

Going back to the Asian disease problem – 200 people will be saved sounds way more appealing than 400 people will die. Our System 1 thinking reacts differently to each, and if System 2 doesn’t intervene to examine it more clearly, then we go with whatever System 1 says.

The thing is that we naturally use System 1 thinking because it’s easier. It’s more efficient. It’s more mindless. And it makes sense because we don’t have time to deliberately think through every decision big and small (or maybe we don’t intentionally do that).

But System 1 theory has a blindspot – prospect theory.

Prospect theory

Anchoring is the idea that we make decisions based on a reference point that we get (often the first one).

Prospect theory tells us that people evaluate their gains or losses relative to a reference point. Basically, people think of their outcomes in relation to the status quo or what they expect, rather than evaluating it as its final state.

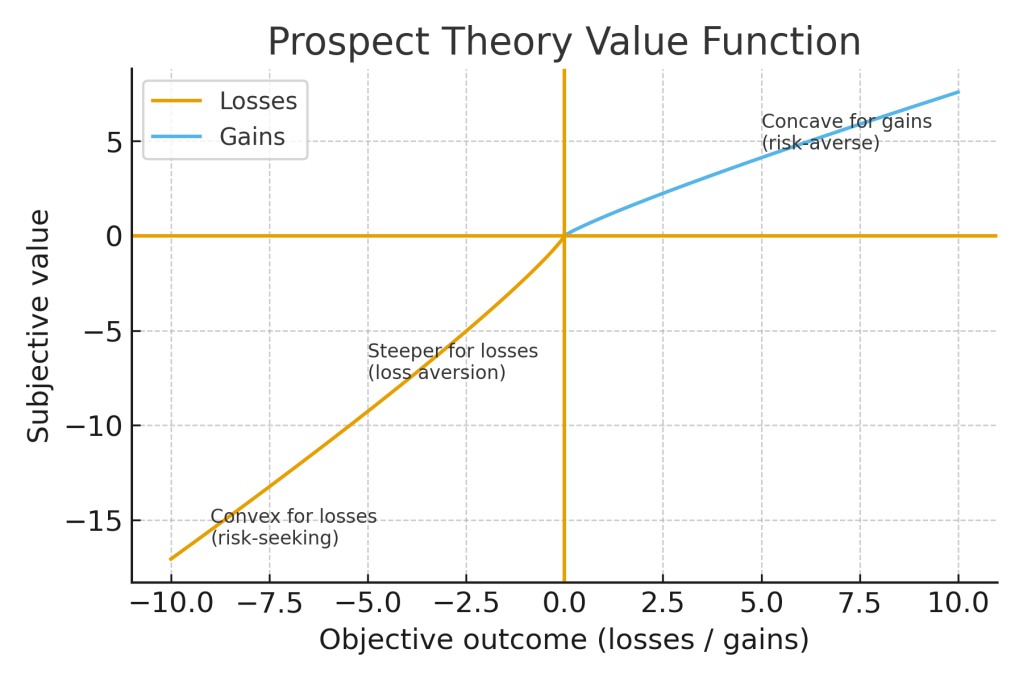

As you can see from the AI-generated graph above, the value that we assign to outcomes is not a straight line. When it comes to gains, the graph is concave – so we are risk averse when presented with gains. But the graph is convex for losses – so we are risk seeking when presented with losses. And that means losses hurt a lot more than gains do, which is why we are loss-averse creatures.

Frames as reference points

And that goes back to how we see things.

Frames – the description of a situation – affects the reference point for a situation. Change the frame/description, and you will change the reference point.

But because we make decisions based on a reference point, it means that our decisions change as well.

So the idea is this. Frames change reference points, and reference points change decisions, and decisions change outcomes. So frames change outcomes.

Paying a $10 late surcharge feels worse than missing out on the $10 early bird discount, even though they’re functionally the same thing. It’s why telling people about a late surcharge is more effective than telling them about the early bird discount.

3 frame checks for busy people

Now that you know about how your System 1 thinking creates frames that affect your decisions – here are 3 ways to make better decisions.

- Redefining the problem

When it comes to reflecting on a problem, you can approach with the perspectives of frames (Schön, 1992). First, you identify the frame – what are the assumptions or interpretations involved? Second, you reframe – how can you look or understand it differently? Finally, you act with the new frame – how can you respond differently with a new perspective?

2. Pause.

Sometimes we just need that pause between stimulus (a problem) and response in order to act more mindfully. That pause gives you distance, allows your System 2 thinking to activate, and the time investment pays dividend in the amount of time you save later with a better decision.

3. Pre-determine frames.

Creating your default frames means you know the most optimal frame to see a situation through. It takes time to think through the kind of frames you want to use – but once you’ve set it, it saves you the effort of thinking later. Suggested frames are:

- Values: Determine what’s important to you so you know what to say yes to, and what to say no to – because of whether it aligns with your values

- Wellbeing: Use positive psychology and determine which wellbeing component is most important to you – Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, or Accomplishments – and make your next choice based on that

- Growth: Is improvement and striving an ideal of yours? Then pick the choice that aligns to that frame.

- Money: Sometimes, it’s all about the dollar. There’s no shame in admitting that money frames your decisions – you can choose quicker.

The picture of your life

As much as I hate to say this, sometimes the frame really makes or breaks a picture. Especially for paintings. But that goes for social media as well.

And that goes for your life as well.

Understanding your decision frames, how you subconsciously use prospect theory in evaluating choices, and being able to change that frame makes all the decision.

Your life is so much more important than a painting. If so much time is spent on the perfect frame for a social media picture, what more spending that amount of time on how you frame things in life?

So choose your own frames – and choose how your life goes.

You might also want to read:

- The invisible nudge reducing your productivity – anchoring (and how to defeat it with adjustment)

- [Movie Review] ‘Avengers: Infinity War’ delivers on all its promises — even if you know how it’ll (probably) end

References

Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice. American Psychologist, 58, 697-720. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.58.9.697

McNeil, B. J., Pauker, S. G., Sox, H. C., & Tversky, A. (1982). On the elicitation of preferences for alternative therapies. New England Journal of Medicine, 306, 1259–1262. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm198205273062103

Schön, D.A. (1992). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315237473

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2000). Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 645–665. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1017/S0140525X00003435

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981, January 30). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211, 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7455683

Leave a reply to Why Your Brain Hates Change: Using Prospect Theory for Productivity – Happiness for Busy People Cancel reply